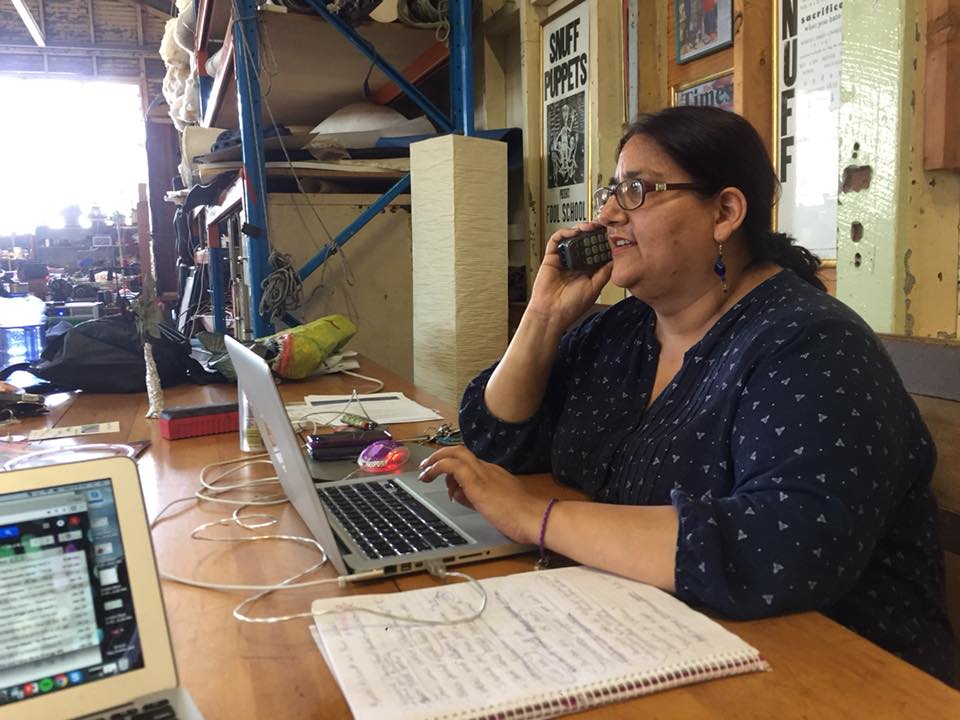

BRACK COMMUNITY LEAD Gracie Teo visited the Snuff Puppets workshop in Melbourne in January 2018. In an extensive conversation, she interviewed Andy Freer, the Artistic Director and Founder of the Snuff Puppets, about his practice of over two decades and how an art or project is meaningfully socially engaged. READ PART 2 OF 2 HERE.

Andy Freer began making giant puppets in 1988 with Splinters Inc., eventually founding Snuff Puppets in 1992. Andy has showcased the Snuff Puppets repertoire of productions, workshops and collaborations to more than 30 countries in Asia, Europe, South America, Oceania and at home.

Following Andy’s principles of deep engagement and lasting legacy, Snuff Puppets have returned multiple times to many of these countries. Andy has created nine theatrical productions, eight roaming acts and two unique workshop models. These works remain in repertoire and continue to be presented to this day.

sometimes you think radical art can be upsetting to some kind of government, values, or people’s ethics. I’m often more surprised that we exist after all this time, because for our subject matter, because we expose the body, and we expose the bodily functions, and we do all these fairly extreme things sometimes, but we’re still here and we’re still doing it.

Everybody, 2015.

G: The Snuff Puppets have been described in The Guardian with this quote: “The Footscray-based company are a welcome antidote to the sanitised Disney Character, celebrating the abject, scatological and the perverse.“ What do you think about that quote?

A: The quote is pretty accurate. We don’t set out to be perverse or scatological; it’s just by our nature, I suppose. Snuff Puppets is an interesting name; it sounds fairly dangerous with its connotations to Snuff movies. Snuff means to die, so it’s got a dangerous edge to it. When you put the word “puppets” with it, it also sounds cute, and has friendly ring to it. But if you think about it, it’s got a dangerous name. I guess that how we float in the juxtaposition between being entertaining, kind of fun, and yet we something to say. And yet we are kind of dangerous, shocking, taboo breaking.

G: On running the company for more than 20 years and some of the effects…

A: I feel like our company are like “outsiders”. We definitely don’t fit like the mainstream. We’ve been around too long to be on the fringe, so we have our own kind of niche place that we exist.

We’ve had funding from the Australian government for many years. It goes up and down. We’re coming out of a downtime, which is another thing about the importance of art, and sometimes you think radical art can be upsetting to some kind of government, values, or people’s ethics. I’m often more surprised that we exist after all this time, because for our subject matter, because we expose the body, and we expose the bodily functions, and we do all these fairly extreme things sometimes, but we’re still here and we’re still doing it.

I think just the overwhelming nature of the big puppets. I think it does have a funny effect on people. Because they (the puppets) are bigger than us, adults, they kind of give us a spark of fear. It takes us back to a childlike state, which many adults would be out of touch with. The puppets have this effect on the public, you see adults running and screaming, being like little children, everyone’s a bit hysterical. It loosens people up.

Because we perform in the street, outdoors in the general public environments, there’s no fourth wall.

It’s like we’re all in this together, and that’s very unusual. It’s not like a street theatre, there’s a circle, with a structure. We move through, the space and we create theatrical moments, as we go. It’s a bit like improvised and responding to the environment.

(…) We helped someone get through their clinical depression, which is very interesting, because there was no drugs or medicines or anything, just a kind of interaction with something that really curious and something that’s not really quantifiable.

G: Yeah, but the audience gets to be a participant as well. They don’t know, and they get co-opted into it already.

A: Yes. You can also watch that interaction as well from a distance and enjoy that. And so there’s many layers of interaction. I suppose the most core one is our puppeteers inside the puppet, so no one can see the puppeteer. We’re very intentional with our puppets, that you don’t every see a human operator, you don’t see someone holding an arm of the puppet, It’s very much so the human disappears, and we work quite hard to hide the puppeteer, when you watch it, you don’t see the human, you see an eyeball (the Human parts of the Everybody performance), you know a cow. People don’t really know how the puppets work. Often people think their robots, or some people still say, ”Is that real?”. Well it’s a real puppet, but it’s not a real cow.

G: There is still Mystery…

A: Yeah, somehow (with Mystery) it can still draw you in, and keep a distance as well, as much as you want to go in (into the performance), you can go in.

We got a postcard once, basically it said that they saw us in a show, the show with the cows and the butcher, and the butcher starts chasing the cows through the audience with a knife and he’s about to kill the cows. And this person, basically that they saw this show, and the cow passed them, and they had been going through depression for a long time, and they felt like after this experience, they could move on, they kind of had this moment that they could let go of something. We helped someone get through their clinical depression, which is very interesting, because there was no drugs or medicines or anything, just a kind of interaction with something that really curious and something that’s not really quantifiable.

I don’t understand it–and there’s doing something hilarious, that moves you physically.

It’s making lots of triggers that you’re not really aware of, you’re just there experiencing. Yeah, it could be interesting how giant puppets help people, with mental illness.