Bite/ Hold/ Release: The Bogeyman’s Hand is a multidisciplinary exhibition featuring the works of Quinn Lum, Adar Ng, and Lin Shiau Yu. The exhibition was held from 1 – 19 August 2019 at Supernormal gallery, collaborating with Brack as a programme partner. This article by Brack’s contributing writer and community lead, Wong Yunjie is the second of two pieces about the artists’ creative processes.

When I was invited to write about Quinn Lum’s Mask-making workshop — an extension of Bite/Hold/Release: The Boogeyman’s Hand, a mixed-media installation exhibition by close collaborators Quinn, Adar Ng and Lin Shiauyu — I did not expect to encounter a brave artist using the arts of mask-making and performance in order to feel, process and reconcile with painful traumas from his childhood. I did not expect to meet someone who, like me, was seeking tools that would help him emerge from the weight of a traumatic childhood with resolution and peace even if that work was to be done alone. I identified quickly with Quinn’s past trauma and present work and thought at first that this article would be about Quinn’s struggle. But after spending time with Quinn, I realised that it was not my place to attempt to position his artwork in relation to his actual emotional state or past circumstances —of which I would never be able to claim full understanding. Furthermore, it became clear that, through his workshop, Quinn’s provocation was to invite the public to confront our own past traumas. What follows then is my response: an account of my own effort at mask-making which gave shape and colour to my own struggles with my mother’s absolute, punitive parenting. The process was intuitive, unplanned, and unanticipated. By the end, I found myself confronted with a visage: a part of myself that was given character by my mother.

Making Fire, then Eating It

Quinn’s installation, Reopening Wounds (2019), spoke to the many layers of struggle he went through in his attempts to free himself from his past. His past was symbolised by a birdcage placed in the centre of the space, containing a tablet facing up, playing a video-on-loop. At a distance from the birdcage, free pigeons stirred and cooed on grass as they feasted on pieces of bread in a video transmitted over a CRT television. Beneath the television stand was a pile of broken bread pieces. This installation was mirrored in the video which played on loop in a tablet placed flat in the cage. In this video, a masked character prowled a living room-set with the same television – a scene within a scene within a scene.

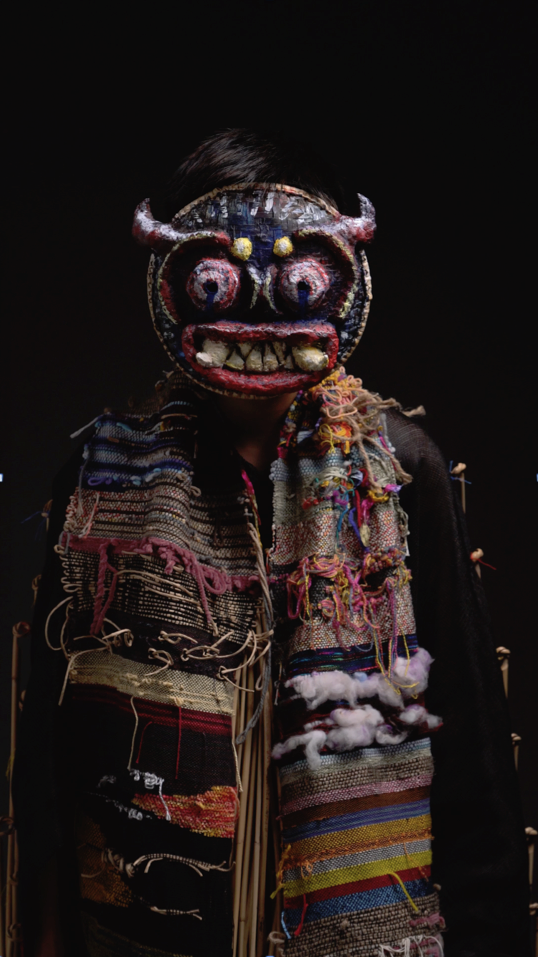

This was his costume:

His “caged” video, playing continuously, captured a powerful, ominous performance full of angry grunts and actions as he tore and tossed bread slices at the birds. The set — perhaps centred around the bread pieces beneath the CRT television — spilled out of the cage, and was replicated, layer upon layer, within the exhibition space.

When I experienced Reopening Wounds a few days before the mask-making workshop, Quinn took me through his process of making the mask and costume himself, while listening to a recording of an interview with his mother conducted by his collaborators Adar and Shiauyu. Thus the mask was born out of a familiar anger sparked by his mother’s reluctance to admit to any responsibility for the emotional wounds he still carries. Instead, she emphasised the idea that if “anyone come to fight with you, you are not supposed to fight back. As long as you fight back, you are in the wrong.”

I feel as if Quinn’s effort at connecting with his shadow-self through performance is an attempt at “fighting back,” an effort in acquainting himself with the anger and fire that was repressed in his childhood. From this “fighting back” emerged a mask, a visage that was defined by an anger so broad, so locked-in, that it swelled his eyes until they were bruised and watering.

At the Intercultural Theatre Institute, I received training in various masked performance traditions including Noh, Wayang Wong, Commedia dell’arte, and Lecoq. My training gave me a profound respect for the power that masks hold in speaking to and drawing out corresponding emotional characteristics within the performer, both when we look into them and when we put them on. Faced with Quinn’s work, I thought back to my own training, how we placed our trust in our Noh and Wayang Wong masters to see qualities in us and choose masks that we would each wear — the characters that we would play — essentially assuming the decisive intermediary role between wearer and the mask.

In addition, Alicia Martinez Alvarez, who taught in the tradition of Jacques Lecoq, taught us a ritual which included a “returning to neutral” by way of a body-scan before and after performing with the mask. I wondered aloud to Quinn and his collaborators if such actions that mark the boundaries of performance vs. life were important so that emotions drawn out by the mask did not linger beyond the performance. It seemed to me that Quinn’s process of making a mask of his angered child-self, then putting it on and embodying it in an improvised performance, was akin to making a fire and then eating it. This was especially so, I thought, since he did not have an intermediary who acted as the mask’s spiritual custodian, nor did he incorporate a ritual that would allow him to draw a clear boundary between masked performance and life. I was concerned how his body and mind might react to the shock of calling into being his fiery shadow self. Quinn then recounted that his nose bled the day after he created the mask.

To allay some of my fears, however, Quinn assured me that the mask workshop would not end by inviting participants to put on their masks and perform with them.

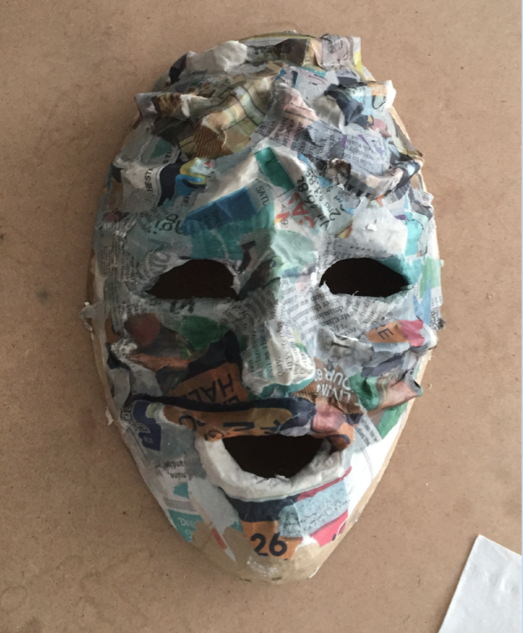

I set out to make my own mask, thankful that I would not have to wear it and grapple with its power through performance. I started with a neutral mask at the workshop on a Saturday afternoon, and set out to give it the shape, contours and finally colours of my own inner self.

Giving Shape to My Mask (Turning Out Differently)

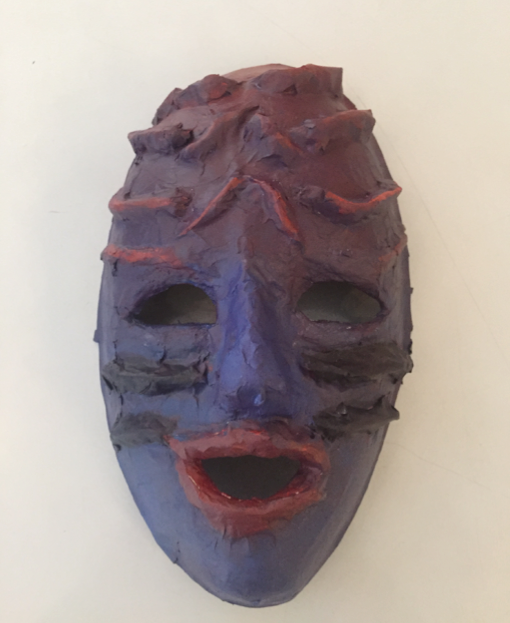

Even by the conclusion of the workshop, I had not realised that my mask bore an uncanny colour resemblance to Quinn’s.

I did not begin the mask making with this end-result in mind. The details got impressed as I drew and moulded, made “mistakes,” accepted them, then allowed myself to be redirected a number of times before arriving at the final mask. As I went on, the mask became a metaphorical likeness of a part of my emotional life, with bulging, fiery-red blood vessels and nerves in the brain, and a picture of calm amusement below.

All I wanted from the outset of the workshop was to peruse the resources available, and to follow the instructions given by Quinn. The workshop was, however, conducted with minimal instruction or facilitation. It turned out to be a largely quiet Saturday afternoon of making, with either Quinn, Adar, or Shiauyu intervening at key transitional moments in order to make suggestions to individuals. I was the first to arrive and was given all the materials I needed to start on my mask. We were not given any prompts as a point of departure, however – on Quinn’s suggestion – I set out by first making a sketch of my mask on a drawing paper. I outlined the neutral mask shape on paper, added eyes and mouth, then closed my eyes to visualise how this mask might look like before I set out to draw it. As I drew, I found myself prompted by little “mis-drawings” or “mis-positionings” which I accepted and used as further inspiration.

‘Turning out differently’ became a theme that afternoon. We could not help noticing with amusement that the artist on my right saw, when he arrived, an advertisement with the God of Fortune on the newspaper in front of him and decided to make a mask in his likeness. Yet, as he shaped, moulded and coloured his mask, he made decisions that made his mask look more like Guan Ti (or Guan Yu).

I was prompted by nothing tangible in the room. I embraced the workshop as an opportunity to tune out the outer world, and tune in to my inner world. I consciously allowed my “mis-takes” to direct me. As I approached completion of the mask’s form, using papier-mâché to mould the lips, nose and whiskers, plaster to mould the nerves and blood vessels, Quinn asked me to share with the group what the mask was meant to convey.

I know that I carry a lot of anger largely held in my thinking-centre. It is anger I often work hard to hide from public view so that it does not manifest in my face or to the world. Yet it was clear that this anger made the blood vessels and nerves bulge on my mask. The artist to my right remarked that my mask resembled the face of a Sith Lord in Star Wars.

My Fiery Lawyer Persona

I strongly resonate Quinn’s aversion to showing anger. I always regarded anger as a force of destruction, a force to fear, and I knew far less about how to accept and harness anger as a creative force without causing destruction to myself and others. Making the mask was a process of setting a path that would give physical form to my inner fire, an opportunity for me to know the personality of this inner fire intimately.

Perhaps anger, shaped differently by differing circumstances, can manifest in different ways. In Quinn, I found a fellow sufferer. While it is not my place to write of Quinn’s anger, I know that I felt deep resonance with his artwork. And just like I know that it is not my place to characterise the punishments Quinn’s mother meted out as ‘abuse’, I find myself also reluctant to use this word when labelling my own mother’s harsh punitive approaches to my “wrong-doings.”

Yet, a part of me would relish it. This part of me is my fired-up thinking-centre. I call this part of me my Lawyer Persona. Objectively, I know that what my Lawyer would consider abusive and criminal was also no more than an outward expression of human flaws under difficult adult circumstances that child-me could not understand. Quinn, myself and countless others in this country have endured childhoods defined by frequent punitive violence. In order to be fully free from this hurt as adults, we would have to confront the trauma, and feel the full depth of it again. For me, to feel the full depth of my trauma is to allow myself to get back in touch with the pain underneath the Angry Lawyer. For, as I have learnt, my anger is itself a defensive mask for the pain I refuse to feel.

When thinking about what my mother did to me, the Lawyer has found every saying, every nugget of wisdom to counter anyone who might suggest that it was forgivable. The Lawyer is pre-emptively reactive to what happened in the past: the frequent canings in red-hot hatred for not doing my homework or not getting the examination grades that were expected. Through her reactive (as opposed to deliberate, ritualistic) caning, my mother applied absolute violence that outrightly denied me the opportunity to share my side of the story – my truth – before suffering immense pain from the cane’s whip. My Lawyer learnt to be similarly reactive, working to absolutely defend myself from unjust accusations or criticisms.

This Angry Lawyer in me seeks absolute justice, a fair and proper hearing for any accusation; seeks absolute punishment, even obliteration of my foes. This Lawyer seeks to defend myself from accusations, seeks to attack absolute characterisations or labels in absolute ways. This Lawyer finds solace in logic and the certainties afforded by rules and reasoning. But interestingly, this Lawyer also values having a cool head to hold all the anger in when ‘in business’, firing up all the neurons and blood vessels so that he can be always scheming and calculating. He is reactive; he is driven by fear. This Lawyer is far from a spontaneous being: he is already expending too much energy maintaining an expression of calm and a semblance of competence for optimal survival, while working in overdrive to keep all forms of criticisms and accusations at bay.

I am not at all certain as to how I made a mask in the likeness of the Lawyer.

Conclusions: Giving Life to the Lawyer

I met Quinn on a separate occasion, two weeks after the workshop, to colour my mask. It was decided that I would paint a blue-purple face that would transition to a gradation of red as I moved up the mask. I had seen and noticed Quinn’s mask. But I did not have any conscious memory of the colours that made up his mask. Throughout the process of painting I felt I was giving spirit to the mask: much like how lion dancers give life to their lion with the tip of a brush.

This time, I made an effort to plan a spread of the right mix of colours to give the gradation effect. I meticulously used the colours and painted so that I would achieve exactly what I wanted; it took 2 hours.

I was a wounded animal while painting. I again relished this opportunity to tune out the real world, and tune into my work and my inner world. The Lawyer had been working intensively just before I met Quinn. It fought to claim some pride for myself with an unreasonable working voice that seemed to be telling me with no subtlety: “I was rubbish. My work was rubbish.” I was made out to be a convict, and the Lawyer felt pressed to step forward to defend intensively. Making the mask was a welcome respite from the intense fire. I felt meek as a sheep throughout.

At the conclusion of my work, Quinn asked me what I thought I should do in order to create a more evenly-coloured mask or a healthier person. The blood-red, I thought, needed to be allowed to seep downwards. I remember thinking correspondingly that I needed to allow myself to express that anger more. But that seemed to imply that the Lawyer should be allowed free rein to mouth-off in anger in order for me to find peace. Now if Quinn were to ask me again, with the benefit of the reflection which followed my mask-making work, I would tell him that making the mask was a starting point for me to acknowledge this anger. It marked the start of a process of healing when I would feel into the pain beneath the mask – beneath the anger – and begin to learn how to forgive.

In parting, Quinn gifted me the set of paint-brushes I used, perhaps in anticipation of the next mask that I might make in this long journey towards reconciliation and peace. Quinn has made more masks that adorn his room. They are his different visages. More masks await me. My other visages have yet to be given shape and contour — or even words.