Brack’s Artist Lead Alecia Neo invited artist Ng Xi Jie (Salty) for an in-person conversation which took place in Feb 2019. The transcript of their conversation was then emailed back and forth between Singapore and Portland, where the artist completed her Art and Social Practice MFA at Portland State University (PSU), which offers a “3-year, flexible residency program that combines individual research, group work, and experiential learning”. She is now the Artist in Residence 2019-20 at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth’s Center for Visual and Performing Arts.

Alecia: Let’s start off with you sharing about your bunion project. Could you share your motivations and what made you initiate this project?

Xi Jie: This project started when I discovered I had chronic bunions many years ago and got really obsessed with curing them. I did a lot of research and tried all sorts of things, from insoles to straps you wear at night and barefoot walking. I found a strong genetic link to both my grandmothers. When there was a chance to create this exhibition because of an award, I decided to delve into bunions in an eccentric and collaborative way. bunion2bunion as a project is constellational and supposed to feel like the crazy research lab of a Bunion Research Specialist, an identity I claimed for myself. It is an artistic inquiry into our relationships with our bodies, beauty, ugliness, defect measurement and DIY-healing. There were casts of my grandparents’ bunions that memorialised my inheritance. There was a publication with writing about inheritance. Each contributor was given a bunion2bunion totebag, from which they distributed the publication in everyday life. I invented the Bunion Measurement Apparatus (BMA) – the poor person’s way of assessing their bunion angle without the hefty cost of seeing a podiatrist. I wanted people to become comfortable with their bodies. Many came up to me curiously asking if they had bunions, but they found the results of their assessment rather pleasing. Other components included a Bunion Archive with bunion photos and writeups; a Bunion Massage Workshop; a bunion awareness poster making session; a world record attempt at the most number of bunions in a single group photo. We had 26 feet with 52 bunions in total, and our application to the Guinness Books of Records was rejected. They said it was too simplistic, meaning anyone could do the same, like make a photo with the most number of eyes or noses in it.

In the middle of the project, I was contacted by three men with foot or bunion fetishes, who agreed to be interviewed. One of them ended up flying to Portland for The World’s First Bunion Panel Discussion, which I organised. The panelists were my foot doctor, a yoga instructor who is also a writer, and Adrian Weber, who describes himself as a foot fetishist with a special interest in bunions. I was very touched that he flew down to be part of this. He does a lot of research on bunions, and tries to understand why he feels this way. The panel was something of a confessional for him. There was also a Hallux Valgus Resource Centre for which I collated information about bunions that was scientific, historical and irreverent. I thought of this as another kind of anatomical or body education.

Finally I did a performance with my paternal grandma, who came to Portland to visit me. It was about acts of care – she folded plastic bags; I massaged her bunions and combed her hair; we applied lipstick for each other.

A: What was your invitation to your grandmother to participate in your work? For example, how did you both arrive at the decision to perform these daily acts, such as folding plastic bags, for an audience in a gallery space?

XJ: It’s something she does a lot. She is very neat and obsessed with folding plastic bags into triangles to keep them tidy at home. I wanted to emphasise the tasks she performs in everyday life. Extrapolating from why I’m interested in bunions, it’s very much about the intersection of art and the everyday. I wanted her to perform everyday tasks in an art space. In this way these tasks become legitimized as performance. In the performance she also taught me how to wrap a bazhang, or Chinese dumpling, which was for me a performance of inheritance. My relationship with her has a lot to do with care. It was really interesting to explore a wide variety of things with the bunion as the root from which a universe sprung, from body awareness activism to things that are more dark and private, kept in the shadow realm, like fetishes.

A: Your work advocates for the vernacular and for people, interests and bodies which might be conventionally unattractive or invisible. There is also a very personal and intimate quality to your projects where you use your own personal history as a platform to discuss various issues. Could you share more about the frameworks for working with people which you have developed for yourself in your artistic projects? What are some of your strategies for negotiating public space and relationships with participants in your work?

XJ: I want to be intimately connected to my work. Sometimes I wonder if it’s necessary to be overwhelmed by the process, because I often feel that way. I’m interested in the little things in everyday life – I try to be intuitive about what is emerging and what to follow. I believe in serendipity – projects happen because you’re meant to meet and make them.

I don’t know if I have developed frameworks, because every social context is different, and every person within that context is different. Perhaps a relational framework begins in mutual curiosity, leads to mutual interest, trust and even affection, then hopefully culminates in excitement at what we did together. We become somewhere between collaborators and friends. It is a dance of intimacy.

It is important to keep thinking about the ethics of any particular project, which would be different from that of another. This includes considering power dynamics among everyone involved (which means thinking about race, gender, class, insider-outsider roles), how the project is funded, how it is documented, and where it is headed.

It is important that participants feel good about working together even if they feel challenged or out of their comfort zones. It is important to question institutional power together. It is also important to allow yourself to not know where it’s heading, and to jump into the abyss together as a bunch of humans trying to experience something different. This is art’s ontology. You can have all the frameworks and proposed aims, but an essential amount of mystery and uncertainty is what makes it art.

A: I recently read the book “What We Made”. During his interview with Tom Finkelpearl, Harrell Fletcher talks about an embodied practice. He makes work which enables him to create the world which he would like to inhabit.

XJ: That was one of my favourite things Harrell said when I was studying in the Art & Social Practice program that he runs. He would talk about deciding what you enjoy doing in life, and then trying to make an art practice around doing those things, whether it’s walking, taking baths or researching whales.

I’ve been thinking about what values artists implicitly and explicitly perpetuate and birth through their work. Beyond content, the entire context around the work – like where it is shown, how it is publicised, who funds it, who sees it – are part of the work too.

If a piece of work is exhibited in an upper class space somewhere like Marina Bay Sands or Ion Art Gallery in Singapore, with a champagne and cheese reception, that becomes part of what the work is. The work cannot be removed from its context.

Because we are performing in every moment, socially engaged art is intrinsically tied to performativity. When artists work in a social sphere, different identities interact in simultaneous performance. Although I don’t think this is what Harrell refers to, being aware of this is some kind of embodiment in practice.

A: Such a collaborative practice often unfolds in real time with real lives, often in ways where we do not have full control over the process. Do you ever feel out of control in your projects? Could you share some of the challenges you’ve faced?

XJ: Often ideas come over me and I feel compelled to make them happen. I both improvise and plan a lot; there is big play between fluidity and precarity. A bane of artists who make collaborative work seems to be the insurmountable number of emails and logistical coordination. But I want to remember that doesn’t have to be the default. What if a project was planned via calls, or snail mail? What if we did spontaneous projects on the street? Logistical coordination is also not separate from the art. The PSU Art & Social Practice program has been working with Columbia River Correctional Institution, a minimum security prison in Portland, Oregon for three years. We started Columbia River Creative Initiatives, and within that I worked with a group of men to create The Inside Show, which we believe to be the world’s first prison variety show. Many emails are exchanged with the prison administration to make seemingly impossible projects like this happen. I see that negotiation – any institutional negotiation – as part of the art happening in the social sphere, shifting it in some way. The initial stage of getting institutional support is just different in the sense that you’re working with the structure instead of individuals as participants or collaborators (although you are working with individuals who shape the structure). I don’t see all that as too different from a painting or a sculpture. All are art if someone says they are.

A: How did you feel about Harrell Fletcher’s film “Blot Out The Sun”? I’m curious about your views on it as I see many parallels to your film work, which also involves a lot of collaboration and creating ways for people to discover their creative potential.

XJ: I love driving past Jay’s Quick Gas in Portland where “Blot Out The Sun” was made so many years ago. To me it’s a piece of conceptual art manifested as a collaborative film. It might start from a score, which goes, “Pick out lines from Ulysses that focus on themes I am interested in. Make some cue cards. Ask mechanics at Jay’s Quick Gas to narrate lines to camera while at work. Piece film together. Screen film at gas station.” Often it starts from designing an idea, then you have to manifest that fantasy.

I’ve been thinking about what forms of labour we exert for our work. For example, the work that artists do applying for grants, making websites, posting on social media, plus all the unforeseen logistics and unseen emotional labour that come with all of that. How can we practice in ways that are nourishing to self? Do you feel you need a lot of alone time?

A: Increasingly so. I’ve found that I’ve needed to carve out space for myself. I also have found it nourishing to share the weight of such labour with my artistic comrades and the folks here at Brack and Unseen.

XJ: Having a community of peers is so important to keep the fire sparking. I’ve been thinking about the choices I make every day, like the food ingredients I buy to cook, to eat, to keep alive – these choices become part of my value system and make me who I am as a person and artist. But I’m still not sure if seeing much of life through art is freeing or ensnaring.

A: It’s both. I share that need to align my values with my daily actions as well. Those decisions and daily calibrations feed back into my work too. Coming back to your projects, could you share what fascinates you endlessly about elderly people? Why have you been drawn to working with them?

XJ: I’m an old soul. I’ve always been close to my grandparents and enjoy spending time with older people. I get a lot out of it and feel or hope they do too.

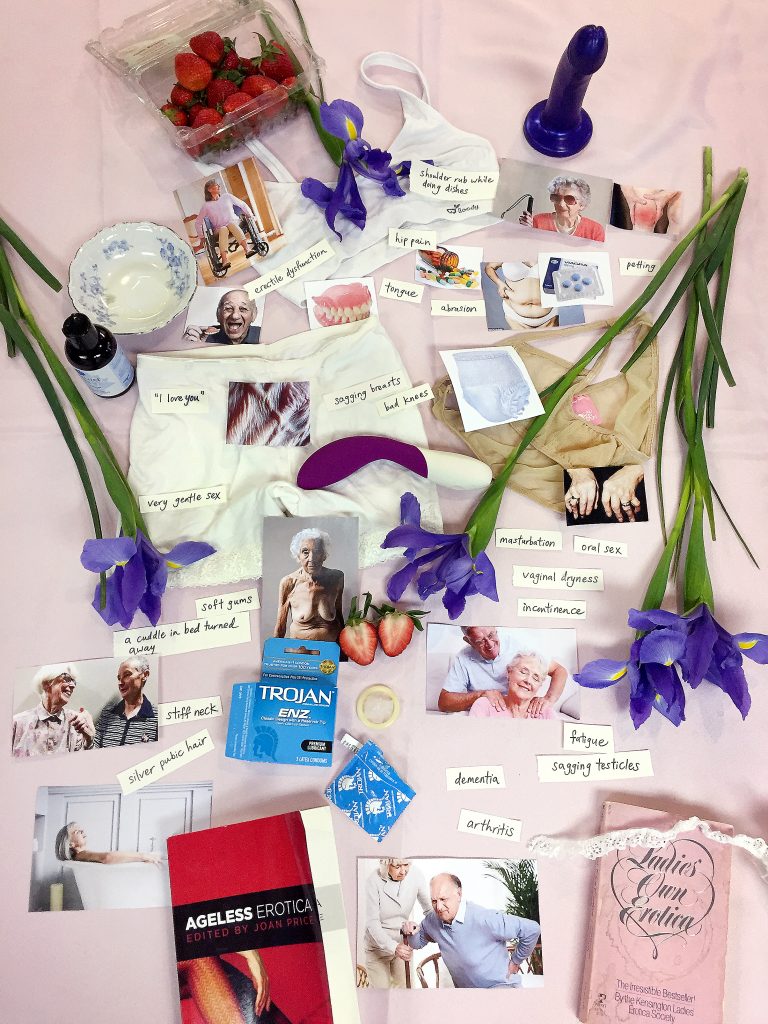

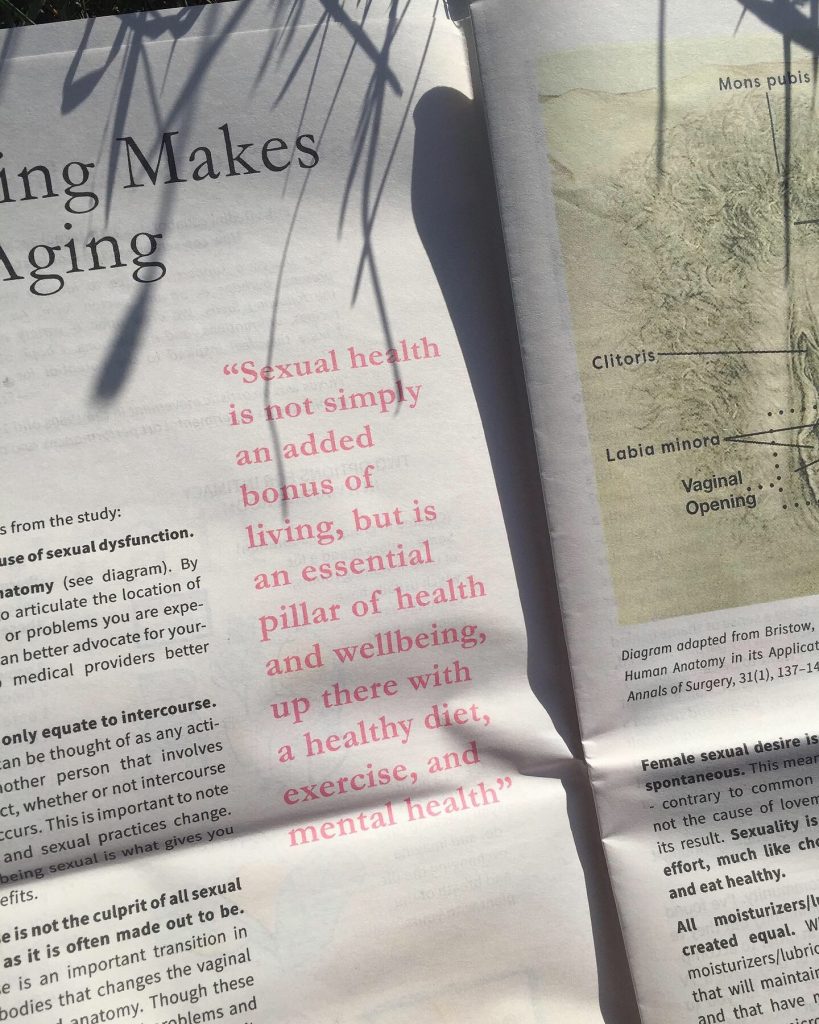

I started a collaborative project called The Grandma Reporter, which is a publication on senior women’s culture. I wanted to explore the universes of older women, perhaps subconsciously to prepare for old age. The first issue was on style. The second issue was on intimacy, in all the ways one can think about this taboo subject. At the Hollywood Senior Center in Portland, Oregon, I worked with a group of women aged 22 to 84. The women were both younger women artists and older women who wanted a space to talk about intimacy in their lives. It was profound for me as a young woman to candidly discuss intimacy with older women over a few months, and facilitate explorations that helped express both individual and collective concerns. My favourite part was starting the Senior Women’s Erotica Club. The publication has a manifesto, a fashion line, senior erotica, opinion articles, public service announcements, and more. We approached social isolation, loneliness and erotic desire in off-beat, eccentric and poetic ways.

A: Thank you for bringing us a copy of The Grandma Reporter! Such a precious piece, with such a diverse range of personal stories and candid interviews. I’ll be very curious how you would approach a Singaporean version of this project.

Social isolation is a big issue here as well. From 2017, I was involved in a project called Both Sides, Now where the artists developed various art projects with seniors in the neighbourhood of Chong Pang. This project was started 7 years ago by local theatre company Dramabox and Artswok Collaborative, and it was borne out of a desire to normalise end-of-life conversations, Women also formed the majority of our participants. Many belonged to a generation of women who have been caregiving their entire lives, putting their families before self. It was a privilege to see how their interest in the arts and our relationships evolved over time. It is also particularly poignant for the artistic team and our participants when life catches up on the very themes which we collective explore. What was the starting point for your project and how did you first make contact with your participants?

XJ: I had formed a strong relationship with the senior center. I’m grateful that the director and center manager were both really passionate about the project and supported me in every way possible. People found out about the project through their friends and an information session I held. There was resistance to talking about intimacy. Some women chided their friends for taking part, but I could understand how if you were brought up to think of sex as dirty, and to not consider what intimacy meant for you (which is still prevalent today), then this project could seem horrific and uncomfortable in comparison to the pleasant activities offered at a senior center. And so we did not expect our publication launch to be packed, especially the women-only discussion on intimacy. We had a group continue to meet after that. They wanted to talk about sexual frustration and learn more about sex toys. Next I want to work with a sex-positive, body-positive, all-gender-embracing sex toy shop to create an outreach program for seniors like the Tupperware and sex toy tea parties that women used to have in homes. The men at the senior center also wanted their own intimacy group and the senior center started working on that. I think people who want to talk about intimacy should get to with their doctors, friends and in support groups.

Another point I want to make is that it’s a fallacy that socially engaged projects which are longer are better and more ethical. Short or spontaneous projects can be equally meaningful and fascinating. I also maintain a healthy skepticism of the ‘artist as saviour’ complex, and projects that claim to positively transform lives or bring good. Easily instrumentalized art is facile and insulting to people’s complex experiences.

Many years ago Mammalian Diving Reflex toured their project All The Sex I’ve Ever Had to Singapore. It influenced me a lot. I’m interested in having The Grandma Reporter prioritise elderly audiences in non-art spaces. I see the Singaporean version as multilingual and more visual than text-heavy. The publication form means considering local seniors’ relationship to print publications, which seems to be more language and race based. I would also love to use it as a chance to collaborate with my peers here.

A: I agree that shorter projects can be extremely provocative, effective and perhaps even offer innovations. However, I do think that it also depends on the intentions of the project. If the objective is for community development, the groups involved needs to be prepared to be there for the long haul, or at least with partners who can offer support once the artists leave. For example, local projects like the community theatre practice by Beyond Social Services, gain their strength from their permanence and sustained efforts in the same place, involving people from the local community and also opportunities for artists from other cities to be involved, over time. However, in many places we also see the opposite problem emerge after artists groups become incorporated in pursuit of sustainability, structurally or economically. The challenge for us is how to maintain the ability to be nimble, experimental and innovative, which is more easily achieved in shorter projects. I don’t believe there is a fixed formula either, and we each have to discover the conditions that enable us to thrive.