COVID Companions is a series of creative pieces featuring snippets of life during COVID-19, with a special focus on the other individuals or creatures who are keeping us company during quarantine, lockdown, ‘circuit breaker’, or whatever your equivalent might be.

3 May, 2020

“Where is home” I ask Natasha, my housemate, as we lounge on her bed. It is a Sunday afternoon, half way through Singapore’s COVID-19 ‘Circuit Breaker’. Natasha is wearing an oversized grey t-shirt and boxer shorts. Her short hair is pulled back with a clip, her face with its characteristic calm and pleasant expression.

“Home is right here, with my housemates,” says Natasha (who is ethnically Taiwanese, has an American passport and grew up in Ho Chi Minh city). “It’s where I pay rent.”

I press Natasha further. “Well, when I go back to Vietnam to see my family, I have to get a tourist visa. So that feels like a reminder each time I go back I’m not really supposed to be there.”

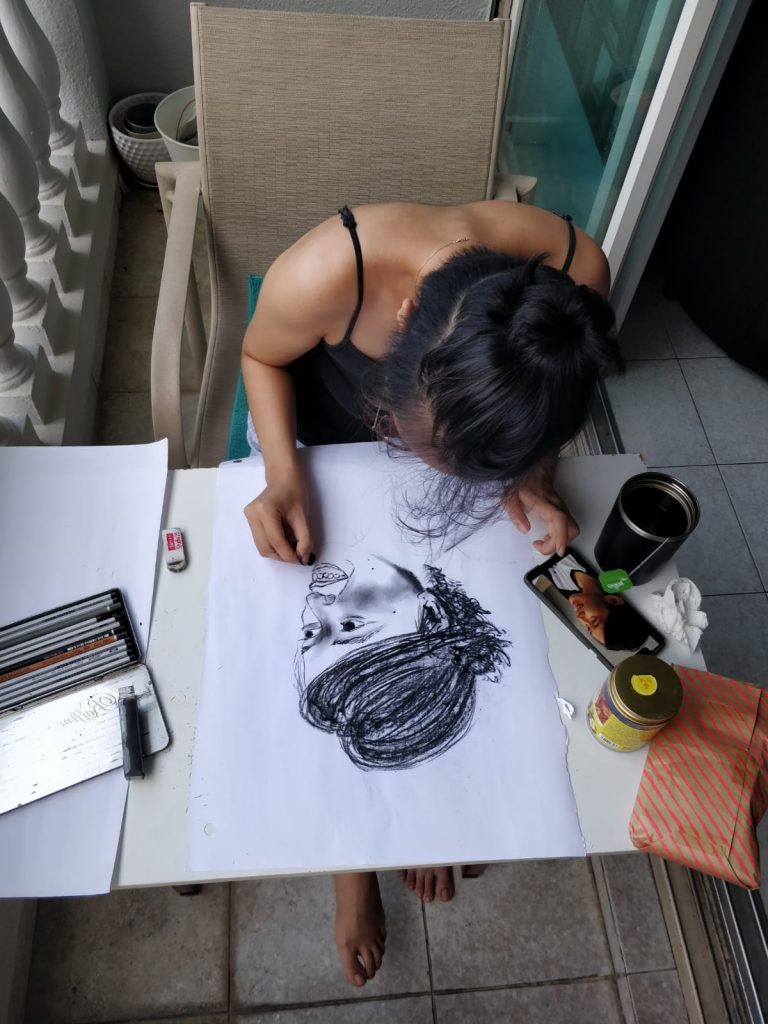

“I guess home is an amalgamation of micro-spaces,” she says. “ In Ho Chi Minh city, it’s waking up late on a Sunday and going downstairs. My dad will be playing really loud instrumental music and making an elaborate salad – romaine lettuce, pomelo, chocolate, nuts, peppers… My mom will be looking at her phone and telling us about the latest health strategy that she thought of.” In Taiwan, it’s waking up late to find my grandpa painting. Once, I remember he was studying a woman in a sports bra from a sportswear magazine. Next thing I knew, he had drawn her into a figure in ancient China… he said he liked her posture.”

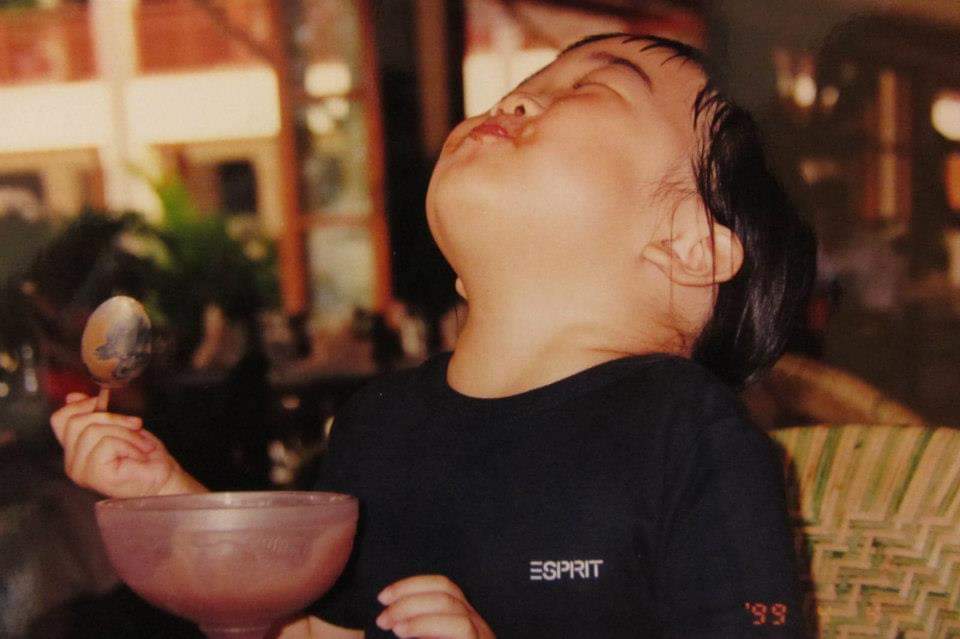

“Taiwan is the place that, growing up, I felt the most loved and accepted. My mouth literally feels more comfortable when speaking Mandarin. I can come up with comebacks a bit more quickly, and I’m a bit more vulgar. Living as an expat family in Ho Chi Minh city always felt very isolating. I remember once we were on the plane back from Taiwan, and I was very very sad to be leaving my family. I was screaming ‘Ahhhh! Noooo! Take me back to see Ah-ma!!!!’ and crying very loudly. At some point, my mom, who could really do nothing more to console me, leaned in close to my ear and said ‘Natasha, do you know what they do to people who cry like this on planes? They shoot them with a tranquilliser.’ I immediately fell silent and sobbed to myself quietly.”

“What about here?” I ask as the afternoon sun streams through Natasha’s sea green curtains. “What micro-space in Singapore is home for you?”

“In Singapore, home is waking up late (you’ll notice a trend) on a Sunday. The windows are open because we don’t like to use AirCon. My housemates and I spontaneously gather in the kitchen to make lunch. Suddenly everyone is stirring and turning on and off the stove and shouting ‘baby, should we add miso?’ ‘do you want to add miso?’ ‘i’m afraid it will be under salted!’ ‘let’s just add Chin-Su later!’ After 45 minutes, we finally make it through. Our dining table always has brightly coloured placemats and a centrepiece with a candle.”

“I sleep a lot, so I miss about half my housemates’ days,” says Natasha as a matter-of-fact. “Sometimes after I wake up at 11am, I’ll eat lunch and afterwards I’ll feel sleepy again and take a nap.” Natasha revels in the ability to sleep during the day, a simple act of resistance against the capitalist notion of productivity that dictates when and how much we should sleep.

With all of this talk of sleep, I notice Natasha’s eyelids starting to droop as she pulls the giant corn-shaped bolster closer to her. In order to keep both of us awake on this lazy Sunday afternoon, I turn the conversation toward Natasha’s love of film.

“I love watching things, but my housemates hate it. I’m always asking them to watch things with me. The other night one of them said ‘maybe… but I’d prefer that whatever we watch doesn’t have a plot and doesn’t have characters, so I don’t get too involved.’ We ended up watching Planet Earth and getting super involved in the intertwined fates of all of the anthropomorphised sea creatures and mountain cats! My other housemate only watches fitness videos…”

“I’m a visual learner,” Natasha explains. “With film, you can just let go and be carried along for the ride. Some films invite instant reflection and insight, and others have a higher barrier to entry – they require more research and work to really understand the Director’s intention.”

As part of the Singapore International Film Festival’s Youth Critics and Jury Programme, Natasha learned more about the process of making and producing films, and the art of film critique writing.

She specifically enjoyed the film The Seen and Unseen by Kamila Andani, which weaves stunning images and dance sequences into a tender narrative about a relationship between a Balinese girl and her very ill younger brother.

“Film is current, it is alive,” says Natasha, her voice quickening. “It has to interact with what is going on right now. SGIFF is so great because it is a lot smaller and more accessible than many festivals. It’s important for us to vary our film consumption and support the upcoming film industry of Southeast Asia.”

When I ask Natasha where she wants to go with her passion for film, she speaks of a regular discussion group that she convenes to discuss short stories and films. The group recently watched Rashomon by Akira Kurosawa. “It’s important that we recognise and celebrate the genius of Asian filmmakers in their own right, rather than constantly referencing the West by saying for example, that ‘[insert Asian filmmaker name] is the Tarantino of Asia.’”

Natasha studied anthropology at a local university. I ask her to explain why, and she tells me of the first anthropology class she ever took – Language, Culture, and Power by the late Professor Barney Bate.

“Every time I walked into that class, my scalp would be numb with excitement. Everything Prof. Bate said changed my worldview completely. His excitement and belief in the value of anthropology was contagious. At the time, it felt like choosing to study it was a decision about identity, it was a choice to take on a lens of the world that seemed much more compassionate than other lenses.”

“Looking back, it may have served me well to take more varied courses. I was comfortable with that way of learning already, I should have developed different skill sets – that would make me more employable now. It was such a privilege to just take a bunch of classes that I found super interesting… But the world just doesn’t work like that.”

“I wish that I would have taken classes in statistical analysis. But I was hubristic. I did things that were fun. But I should have done more things that were not so fun. That is one life lesson I take away from all of this.”

I ask Natasha whether she might consider a job in academia, given her passion for learning, thinking, writing, and ideating.

“I’m very intellectually promiscuous,” she says, shaking her head. “If I wanted to go into academia, I would have to really hone one discipline or research focus. I don’t want to repeat my same mistakes. I’ve had my fun.”

I press Natasha on why she feels life should no longer be fun.

“I lack discipline,” she states resolutely. “You know what I mean, as my housemate. I wake up at 11am. You wake up at 6:30. By 11am you’re wondering what else to do. Then I wake up and I’m still drowsy and I give you a hug. Then I go back to sleep. I’m too indulgent.”

“Do you think indulgence gives your life meaning?” I ask.

“In some ways. It certainly gives me a lot of pleasure.”

I poke further. “What’s the meaning of life? Could it be pleasure?”

“You’re walking me into an existential crisis…” she says. “I think it may be partly about pleasure, but you need a balance. I’ve never been balanced. Sometimes I have a lot of hype in my life. I’ll hype myself up about drinking a nice cup of tea. Other times though, I feel very bored. At the end of the day though, after all the hype and all the boredom, I wonder ‘what did I really achieve?’ ‘what impact did I have?’.

“There are things that I’m escaping from,” says Natasha, looking down “… like the real world, the news, my future. I’m very myopic, literally and figuratively.”

“Some people would call that ‘present.”

“A bit too present.”

“What is one thing you’re good at?”

“I’m good at watching TV. I’m good at watching slow films. I’m patient.”

“What else?”

[silence]

I tell Natasha one thing I think she’s good at. She’s brilliant at having fun. She’s skilled at making mundane spaces and processes precious and memorable. I remind her that just yesterday she curated an entire YouTube playlist of karaoke songs and bought cider so that we could have a karaoke night to cheer up our spirits. She’s skilled at bringing pleasure into each moment. She’s mastered the art of delight.

Natasha characteristically deflects the compliment, explaining that she doesn’t deserve any credit, “… No, it’s really my housemates that bring this fun side out of me,” she insists.

“I’m good at having fun when I feel safe,” says Natasha. “I only take ownership of the situation when I feel safe, and I feel safe when the people around me actively support and nurture me. Simple things, but things that are not a given.”

Natasha gets up to turn on the fan then comes back to her bed. We both yawn and call to our third housemate to come join a cuddle puddle. Three little kittens, sisters, housemates, friends, fall gently into slumber. A sweet act of collective resistance.