Reflections on Brack’s To Gathering: Laying the Table Bare

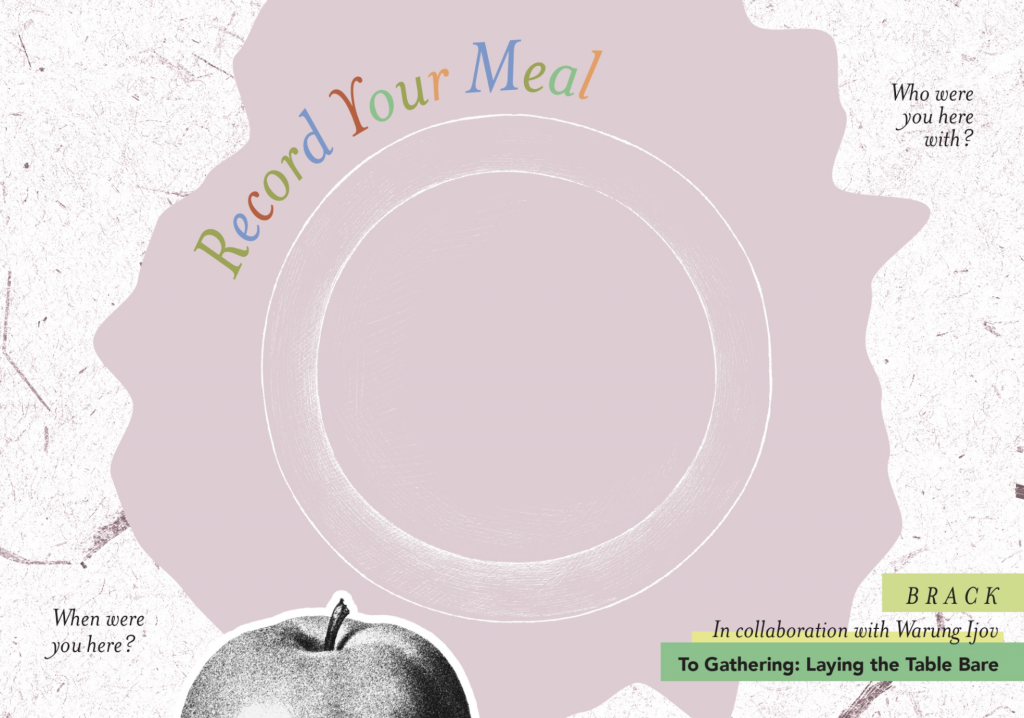

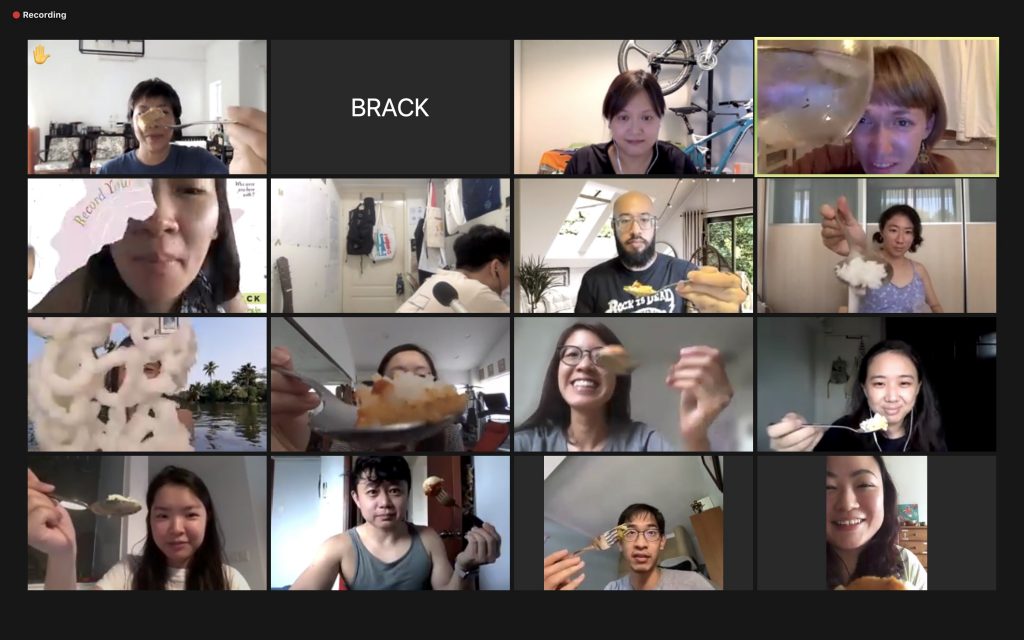

Laying the Table Bare was the most recent iteration within our To Gathering series – an ongoing series of experimentations and research-workshops exploring acts of gathering and radical hospitality amidst conflict and disruption. Designed around the origin and operations of Warung Ijo, an Indonesian vegetarian eatery in Singapore, the work unfolded in two parts: a physical installation hosted at the eatery, and a series of digital lunch gatherings with food delivered from Warung Ijo to the audience members’ houses. To Gathering: Laying the Table Bare was presented as part of the Singapore International Festival of the Arts (SIFA) 2021.

Last week, the Brack core team came together for a rich conversation about what we learned from the process of creating Laying the Table Bare. What follows is a presentation of some of the insights, questions, and provocations that emerged.

For context, in conceiving Laying the Table Bare, we expanded our notion of ‘host’ to include people (and groups of people) who have professionalised the art of hosting – in this case the owners and staff at Warung Ijo eatery. We were curious about whether these people thought of themselves as hosts and their work as hosting, and what dictated the choices they made (creative, pragmatic, or otherwise) in terms of curating space and experiences for their ‘guests’. We sought to undergo a process of ‘laying the table bare’ – peeling back the layers of professionalism and bureaucracy to reveal the host’s intentions, visions, personal history, and motivating ethic.

“Laying the Table Bare” – How can?

Concretely, this meant hundreds of WhatsApp messages exchanged with the founders of Warung Ijo. It meant a handful of visits to the eatery to get to know the staff, and time spent before and after discussing what questions were appropriate and fair to ask. It meant translating the abstractions sometimes present in art-making into practical, concrete language for our collaborators. And thereafter, it meant a lot of time spent (on Zoom calls / in rooms with each other) trying to piece together the snippets that we were uncovering into something compelling, while confronting the sheer magnitude of missing information that we did not and could not have access to.

“We wanted – perhaps more than anything – to avoid perpetuating an extractivist dynamic, one in which the staff at Warung Ijo felt like their stories and lived experiences were being used, taken out of context, profited off of.”

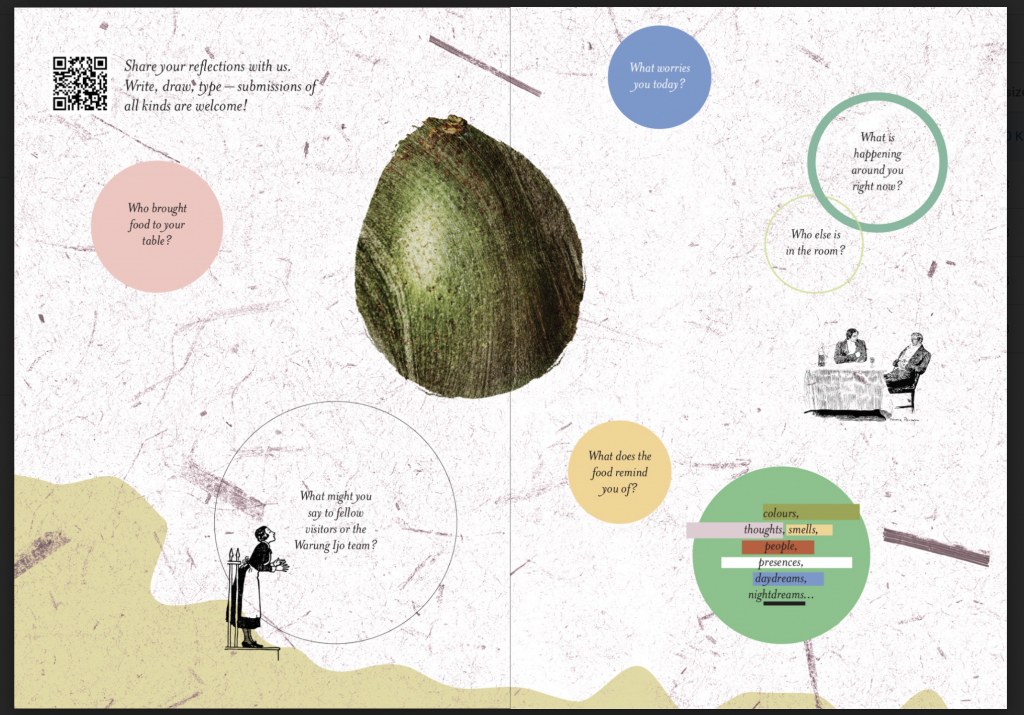

During our reflection, we discussed the work’s title. Manifold questions surfaced. “Had we been too audacious to presume that we could lay the table bare?” “Which table, anyway?” We arrived at the realisation that in titling the work “Laying the Table Bare,” there was an important emphasis on the process of laying, an acknowledgment of the inevitably of a non-arrival in this endeavor. There would never be a moment when the story had been fully told, the truth fully revealed, the table fully laid bare. Instead, Laying the Table Bare was an invitation for the audience to join us in a process of unpacking, a process of deeper noticing of things – the food on your plate, the things in the space around you, the people and systems and histories and mistakes and serendipities that made this moment in your life happen.

This led us to an important insight around the nature of relational art-making processes. If the process of making art is to center the relational, it must emphasise, account for, bend to, and prioritise relationships while maintaining constructive criticality. Practically, this might mean asking questions like “How can we create relationships across sectors in a way that feels authentic?” “What value will Warung Ijo get out of being involved in an arts festival?” “How do we show up to the collaboration with a clear intention rather than a Plan with a capital P?”

We wanted – perhaps more than anything – to avoid perpetuating an extractivist dynamic, one in which the staff at Warung Ijo felt like their stories and lived experiences were being used, taken out of context, profited off of. As such, we focused more on being sensitive to the people and context within which we worked, and less on being fixated on a particular outcome. A significant amount of our energy went into considering what ‘success’ might look / feel like from the perspective of our different stakeholders (the team at Warung Ijo, the artist liaisons and programmers at SIFA, the audience that would witness and experience our work).

Relational art-making also means embracing the reality that working with humans means acknowledging – and indeed even integrating – the full spectrum of unpredictable, messy human experiences into the process of art-making. The staff at Warung Ijo were often extremely busy with the operations of the eatery. Understandably, it was not easy to make time to speak to us about what their ideal gathering would look like, or to explain the intricate systems of jastips responsible for supplying the ingredients to their eatery. There were ingredients in certain recipes that needed to remain confidential in order to protect Warung Ijo’s coveted trade secrets.

“…we designate and invite the audience into a ‘play frame’ of sorts, a micro-world with its own terms of engagement, a space in which different power dynamics are at play, and thus different things become possible.”

The food delivery service ended up devolving into frantic phone calls to each motorcyclist or driver on the morning of our shows, coordinating drop-offs and figuring out why one audience member (who happened to be the festival director) still didn’t have his food. Moreover, one day before the opening of SIFA, Singapore announced that dining in restaurants would no longer be allowed due to rising numbers of COVID-19 cases. We were devastated that our site-specific installation (with soundscapes and video clips and interactive activity booklets) would not be experienced during the course of the festival after all.*

But – in this process of navigating awkward first conversations, fitting answers into questions, relating across lines of occupation, class, language… were we not indeed laying something bare? In the end, perhaps our most important yet modest gesture was making a work that reflected the messy, dynamic, constrained, idealistic and imperfect nature of the individuals and relationships involved.

What exactly is Brack doing in To Gathering? Got art meh? Where?

As we considered the relational process of making Laying the Table Bare, we asked ourselves – ‘What are we really doing with our work? What role are we playing?’ This led to a fruitful discussion about the creative modality that has been central to our To Gathering series.

We see our work in To Gathering as a process of designing experiences that draw attention to, and invite a deeper noticing of the many ever-present layers that comprise our reality. As instigators / interveners, we orchestrate encounters where people can ask questions with us, and then create conditions wherein they can discover their own answers, make their own decisions, and undergo their own transformation. Building upon our previous collective world building workshops, through our interventions we designate and invite the audience into a ‘play frame’ of sorts, a micro-world with its own terms of engagement, a space in which different power dynamics are at play, and thus different things become possible. Then, through emphasising fiction and imagination over fact within that play frame, we invite (and indeed necessitate) that audience members step into their own agency, as active players in an emerging game.

Moreover, through creating micro-worlds with new rules and inviting audiences into them, we attempt to provide simple scaffolding that empower people’s most basic yearnings – to connect, to share, to be seen. It can be easier to show people the messy corners of your home, to tell a story about your grandmother’s cooking, to share what you’re deeply grateful for… when prompted to do so, when it is part of a game and there’s no way forward but to keep playing.

The context of art is a ‘play frame’ in itself which is useful to us, because it invites curiosity, directs attention, and encourages people to approach the work with patience, questions, and a belief that there is meaning to be found.

A closing thought on Radical Hospitality

At the end of our conversation, we spoke about how creating Laying the Table Bare had contributed to our understanding of this elusive term ‘Radical Hospitality’ . Our discussion centered around the etymological essence of the word ‘radical’ – a return to the root of something. We mused about how the simplest acts of decency, a whispered reminder, a quiet invitation, a modest gesture, can perhaps be the most radical acts of all. Not just because they invite a stripping away, a return to fundamental questions, but also because they peek out from / flow under / soar above the manic, loud, punchy, proclamatory, decisive, dominating discourses that seem ever-pervasive and popular. As Jevon elegantly put it – “it’s damn radical to be quiet amidst the noise lor”.

*We are in the process of discussing with Warung Ijo the possibilities of showcasing the project when dine-in restrictions are lifted in Singapore.