A conversation with Singapore International Foundation Arts for Good Fellows Apurva Shah & Yehuda Silverman

By Kei Franklin

The Arts for Good Fellowship (A4G), organised by the Singapore International Foundation (SIF), is an annual programme dedicated to growing the Arts for Good ecosystem by fostering a community of practice that harnesses the power of arts and culture to create positive social change. The A4G Fellowship brings together artists, arts administrators, creatives, and programmers from the social sector from around the world to take part in an exchange of ideas and best practices across a five-month period.

The most recent edition of the Fellowship was offered digitally, with 32 Fellows from 12 countries joining the SIF team and speakers from Singapore in late September 2021. They spent one week learning together, sharing their skills and experiences through a series of virtual presentations, workshops, panel discussions and working groups. From September 2021 to February 2022, Fellows reconnected through monthly webinars in order to build their capacity in arts innovation, such as in cultural mapping and creative facilitation models. In February 2022, the Fellows reconvened for the second phase of the Fellowship, this time hosted by SIF’s partner in India, NalandaWay Foundation. The India Programme included implementation of four digital community projects that the Fellows collaborated on over the past months for vulnerable children in various Indian cities.

This fourth iteration of the Fellowship focused on the theme of Arts and Well-being for Children and Youth in a Digital Future, exploring the intersections between the arts and technology in enhancing access and achieving social impact, and how the arts contribute to the mental, social and emotional wellness of young people in a digital age.

Introducing Apurva & Yehuda

Last week I had the pleasure of sitting down with Apurva Shah and Yehuda Silverman, Fellows from the Singapore International Foundation Arts for Good Fellowship. From three continents and across three time zones, we spoke about how working with youth can heal our inner child, the power of play to resolve conflict, and how our imaginations make us human.

Apurva is a theatre-educator who works with youth in villages throughout northern India – in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Himanchal, and Madhya Pradesh. In addition to her work in theatre, she has a background in film and documentary making. She is bashful when it comes to taking complements and has a smile big enough to fill the screen. Yehuda, who is currently based in Florida (USA), calls himself a peacebuilding pracademic (practitioner-academic) with a PhD in conflict resolution and a background as a Guardian Ad Litem. While not a formally trained artist, Yehuda integrates art and creativity into all the work that he does. He has a startling and contagious laugh and a generosity that shines through.

When we spoke, Apurva and Yehuda had just finished the India portion of the Fellowship, which entailed working with other Fellows to design and implement a digital community project for a group of youth somewhere in India.

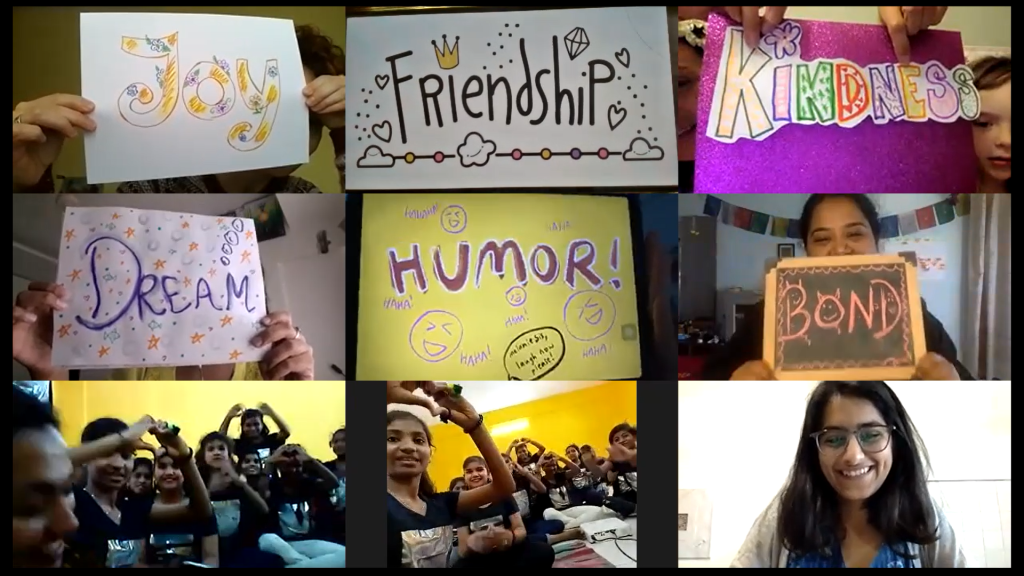

Apurva’s project, Project Sakhi, took place in Bangalore. The Fellows worked with 21 young women – ages 13 to 17 – who live in a Children’s Home for girls. They are mostly children of migrant labourers and trafficked women, and many are orphaned. Throughout a series of workshops with the Fellows, the girls created characters of superheroes that live in a fictitious land called Sisterhood Island. These superheroes embodied the strengths and ‘superpowers’ that the girls saw in themselves. The workshops culminated in a costume parade of the different characters of Sister Island, which gave the girls an opportunity to take on the different roles that are central to performance-making.

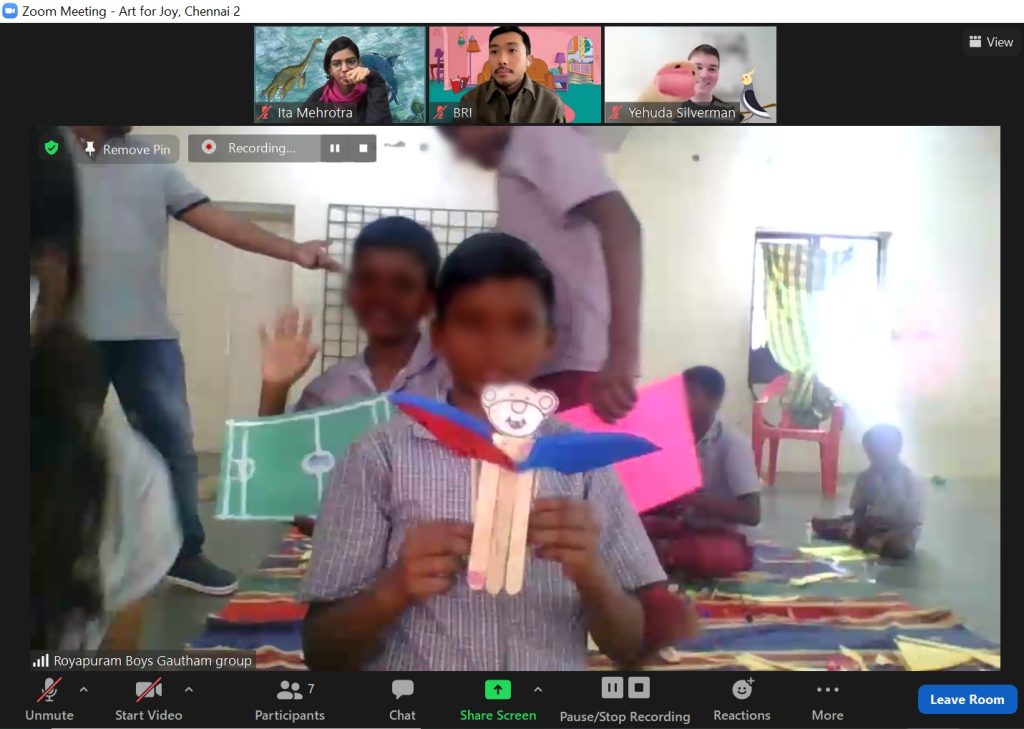

Yehuda’s project, Art For Joy, took place in Chennai. Fellows worked with 23 boys – ages 11 to 13 – who live in a Government Children’s Home for boys. They have all experienced histories of trauma, abandonment, and familial conflicts and complexities and many are orphaned. Throughout the project, the boys created their own puppets who then featured as characters in a culminating performance. Some of the puppets’ characters were infused with qualities that the boys saw in themselves, and the stories that played out in the performance featured methods of conflict resolution that the Fellows had taught the boys through a series of workshops.

When hearing Yehuda and Apurva describe their community projects, I was struck by how they had used creative media (puppetry and superhero storytelling) with the youth to explore themes like confidence, conflict, and the values that define us. I wondered what Yehuda and Apurva saw as the strength of using these creative forms as compared to simply introducing these questions in the form of a conventional ‘lesson’. For example, Apurva could have asked the girls “stand up and tell us what your strengths are,” but instead she invited them to create superheroes that just happened have the same strengths as they did, in the form of superpowers. Similarly, Yehuda could have asked the boys “tell us an example of when conflict has shown up in your life,” but instead he invited them to create puppets who would then tell stories of conflict. I asked Apurva and Yehuda to reflect on this element of abstraction, this choice to have the youth tell their stories through the mouthpiece of another character.

Apurva said: “The human mind is wired to understand through stories […] It is important to give examples if you want someone to understand something. If you want to describe what an elephant is to a child, you need to tell her a story of an elephant. Everything is a story only, nothing else.” Apurva mentioned how often children understand and express themselves through their toys, which are puppets of sorts. As such, creating external characters as proxies for understanding and expressing themselves is a technique that young people are very familiar and fluent with. “Creating superheroes that embodied their strengths led the girls to feel confident,” said Apurva, “as they could see that their strengths are enough to make them superheroes. Confidence is essential for imagination, and imagination is important for everything. As Lord Shiva said, ‘imagination is what made us humans.’”

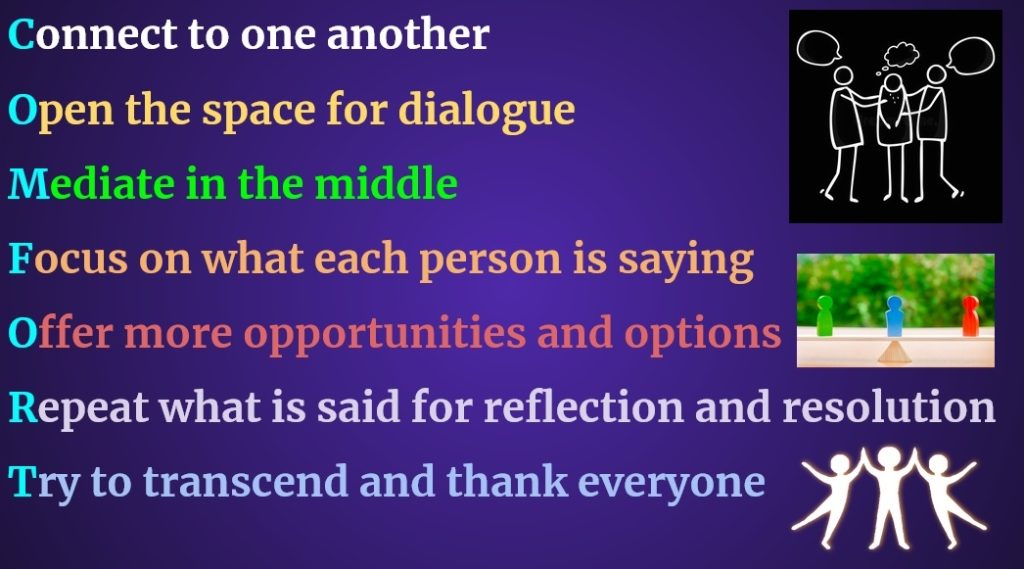

Yehuda expanded on this by saying: “The kids had gone through a lot of trauma, so being creative gave them a chance to escape into a whole other character and create a whole new story.” Puppet-making and performing gave the young people a respite of sorts, a chance to not only immerse into a less wrought world than their own, but perhaps to view their own stories through a new lens. “Being able to express themselves through a puppet might have felt more comfortable than just telling their stories outright.” Yehuda had taught the boys some techniques of conflict resolution as part of the workshops.

As such, the boys could practice integrating alternative ways of solving conflict into their puppet stories and were invited to imagine different possible ways that their own stories could have unfolded. “At the end of the workshops,” said Yehuda, “we asked the boys ‘what would you like to say to your puppet?’” They took this very seriously and there were some heartfelt moments where they acknowledged the parts of themselves that they poured into their puppets and were able voice the ways in which they hoped to bring what they learned forward into their lives.”

Upon hearing Apurva and Yehuda’s reflections, it struck me that – through inviting the youth to reflect on and express themselves through the proxy of superhero characters and puppets – Apurva and Yehuda created a certain amount of distance which invited safety. It is crucial that we are able to feel safe in order to be creative. Indeed neuroscientists, trauma specialists, and bodyworkers alike reflect on how fear narrows our minds and (physically) diminishes our ability to be creative and think of multiple possibilities. In order to be expansive, we need safety. In order to open ourselves up to possibilities we might never have imagined, we need to know that we are held. Through their skilful integration of play, joy, and silliness into their work, Apurva, Yehuda and the other SIF A4G Fellows held a container in which the youth not only felt safe, but felt safe enough to be brave.

Throughout our conversation, I became curious about how the India Programme component of the Fellowship – working directly with youth in communities – might have impacted Apurva and Yehuda both on a professional and personal level.

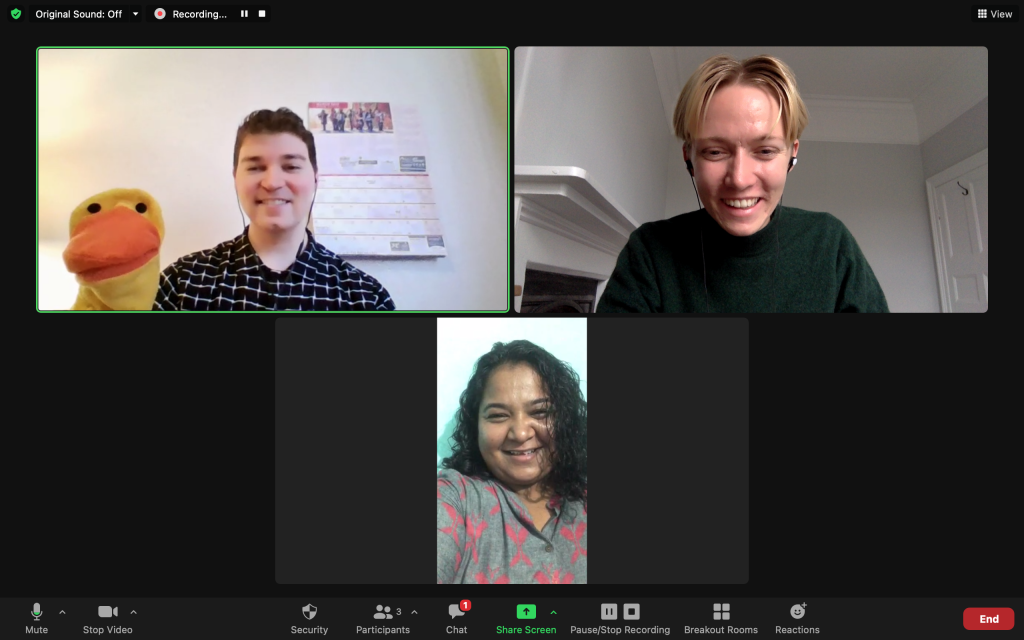

Yehuda shared — “During the workshops, I often found myself asking – ‘what would my inner child need right now?’ […] Our voices are often suppressed as children, and I felt it was important to give the boys a chance to open up and feel safe and included while expressing their own voices.” Yehuda reflected on not having much opportunity to be creative during his own childhood. “The Fellowship was one of the most important experiences of my life,” he said. “Sometimes the work I do is very restrictive […] the Fellowship encouraged us to drop any barriers that we might have. I realised that it’s okay to be vulnerable. Because when you do art, your whole self is really put onto a platform for other people to view. The Fellowship connected me to a part of myself that I did not have significant access to […] I discovered that I can actually bring humour into my professional life.” (At this point in the conversation, Yehuda introduced Dr. Quackers, a duck puppet who he created during the Fellowship and who has been making frequent appearances in his professional meetings since). “I find that people can breathe a bit more when Dr. Quackers enters the room.”

Apurva added — “I find that working with youth, I have more faith in humanity. When I was very little, I was in a very strict school which only allowed for specific students to take part in creative activities. I was constantly told ‘You cannot be an artist’ and I began to sincerely believe that I’m not very good at art. It feels important to be working with young people to help them see that they can all be artists.”

Reflecting on the Fellowship as a whole, Apurva shared that she was provoked to think deeply about many questions she had not previously considered. She became much more confident in her ability to use technological platforms to enable meaningful remote collaborations, and now feels she can be more productive in her work with communities despite barriers of connectivity. Yehuda was also impressed by the power of technology and the depth of the connections formed despite the virtual nature of the Fellowship. “I was affected by the importance of words” shared Yehuda. “Words can make or break trust, and – even across vast distances – can create a powerful space of acceptance and love.”

Both Apurva and Yehuda are taking from the Fellowship new friendships and the promise of future collaborations. From our conversation, I am taking 1) a sense of renewed hope, because young people around the world are able to work with people like Apurva and Yehuda, 2) a sense of gratitude that a platform like the SIF A4G Fellowship exists to bring them together, and 3) a final question — ‘what would I like to say to my superhero puppet?’